13

Key Concept

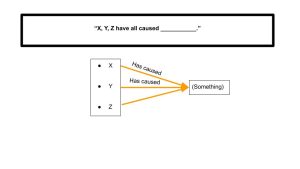

Causal Argument: argues that there is a cause and effect relationship between certain conditions

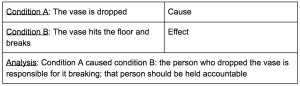

Sometimes the cause and effect relationship between certain things can seem really clear cut. For example, if someone drops a vase, and the vase hits the floor and breaks, obviously that happened because the person dropped it. Or we can think of this scenario like this:

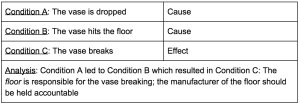

Seems pretty straightforward, right? But what if it’s not? What if the cause and effect relationship between the vase being dropped and the vase breaking is a little more complex? Let’s continue to explore this hypothetical situation more: couldn’t we also argue that the vase broke not because it was dropped, but because it hit the floor? If so, then our analysis of this situation would look a little different–maybe something like this:

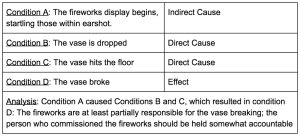

Still seems pretty straightforward? Well, it certainly is if you’re considering only the direct causes of the vase breaking. What if we also consider indirect causes of the vase breaking. By bringing in indirect causes of the vase breaking things get a little more complex. For example, what if, through further research, we learn that the vase was dropped because the person holding it was startled by a nearby fireworks display (an indirect cause)? Our analysis then might look something like this:

Through further inspection, things could possibly become increasingly complicated. (Remember, as good researchers, it’s incumbent on us to always dig deeper when we’re researching!) For example, perhaps the vase hit a hardwood surface, as a opposed to a softly carpeted surface. Is the interior decorator implicated in things now? Are the interior decorator’s design choices an indirect cause of the vase breaking? Or, perhaps the person who commissioned the fireworks mailed out an announcement to notify those nearby that the fireworks would be happening and the person holding the vase thought it was junk mail and threw it in the trash without reading it. Is the holder of the vase, then, responsible? If so, it looks like we’re right back where we started!

While we’re not here to adjudicate who is responsible for the vase breaking, what the above hypothetical situation illustrates is that what we often think of as a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship can often be more complicated than it seems upon further inspection. Equally, this scenario illustrates how one can structure a causal argument, which argues that there is a cause and effect relationship between certain conditions.

And while the above scenario might seem fairly innocuous, that’s not always the case for causal arguments in the real world. Take for instance the 1985 firebombing of the MOVE house in West Philadelphia. MOVE is an organization that began in the early 1970’s. They practiced a communal lifestyle and argued in favor of justice for all, specifically for racial justice. After several years of growing tensions between the Philadelphia Police Department involving, among other things, the death of Officer James J. Ramp, an explosive device was dropped on the residence where the MOVE members lived. That explosive device detonated, and the building subsequently caught fire. The fire was deliberately not extinguished immediately. Eleven members of MOVE died in the blaze, including five children. Furthermore, the fire spread to the rowhomes of the nearby residents, destroying them as well.[1]The official commission that investigated this event determined that while the city’s handling of it was “unconscionable,” no one from the city government was charged with any wrongdoing.

This event raises a number of questions about causal arguments–questions that are still debated to this day, pertaining to who should be held responsible for the death and destruction caused by this event:

- Should the then-mayor of Philadelphia (Mayor Wilson Goode) be held responsible, since he approved the bombing?

- Should the Fire Commissioner be held responsible for not taking the initiative to quickly stop the blaze once it started? Or should the Police Commissioner be held responsible for not determining that the fire was a true danger to many, which he should have communicated to the Fire Commissioner? (Both the Police Commissioner and Fire Commissioner were at the scene, monitoring the events of the day.)

- Do the members of MOVE share some of the responsibility for engaging in actions that could have been perceived as having provoked the police and the city? Equally, do they share some of the responsibility for failing to evacuate the building once it caught fire?

Again, it’s not our responsibility to adjudicate this particular situation, but what’s important is that it raises a number of questions about causal relationships and highlights the way that the circumstances that caused an event can open be open to interpretation.

For our purposes, however, here is how we can think about making causal arguments:

Within your general topic, identify an issue about the causes or consequences of a particular phenomenon and create a thesis that asserts which cause(s) or consequence(s) seem most relevant for better understanding and responding to the problem. Be careful to distinguish between types of causes (direct vs. indirect), to acknowledge other important causes/contributing factors, and to avoid inductive fallacies in your reasoning. To generate ideas, consider the causes or consequences of trends related to your topic, or the consequences of actions being taken or proposed.

Recapping the main ideas behind causal arguments:

- Causal arguments argue that there is a cause and effect relationship between things

- Causal arguments use evidence to say that one condition contributed to the existence of another condition.

- To learn more about the complexities of the MOVE bombing, check out David Osder’s 2013 film Let the Fire Burn (Zeitgeist Films). ↵